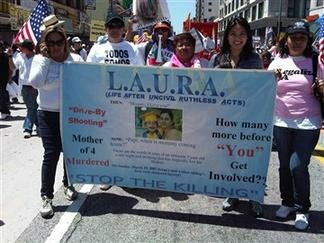

Courtesy LAURA

Video: Click below to play

Adela Barajas pulls a picture from the front of her computer. A young Latino man smiles back with buzzed hair, a mustache and a crisp light blue button-up shirt.

“This is Tony. He’d just turned 18 in October,” Barajas says.

Tony was shot as he rounded the corner near his house. He was walking to a party, which was unusual — he rarely went out at night. His mother watched him walk to the corner, get shot, and take a few more steps before collapsing.

After he died, Tony’s mom was referred to Barajas. Like many before her, Barajas helped Tony’s mom negotiate lower funeral costs and found her counseling to endure the loss of her son.

Barajas searches for resources to help the families of homicide victims because her motto is “when a homicide happens, the whole community is affected.” Barajas knows what families who lose their loved ones need: four years ago, she lost Laura.

Barajas’ sister-in-law, Laura Sanchez, was driving with her 5-year-old son Brian in the car when a stray bullet killed her. She struggled with her grief while she dealt with funeral arrangements. The process was difficult, but it inspired her to form Life After Uncivil Ruthless Acts (LAURA) in her sister-in-law's honor.

Through the program, Barajas might help families fill out paperwork or find a reasonable funeral home; she might arrange for grief counseling or help find outlets to keep younger families from taking their grief to the streets.

“I help them out so they aren’t re-victimized,” Barajas said.

Grief — An Unending Fight

Processing grief through city-supported services — such as grief counseling — can be difficult given Latino families’ resistance to therapy, Barajas said. Being a victim of homicide is a life-damaging experience for the whole family, but families are often uninformed of services that would help them address their anger and emotions. Some hesitation to pursue city resources stems from families’ fears of being reported to immigration services.

But without an outlet, youth are susceptible to influence, which could lead to crime and gang involvement. After Laura died, her oldest son, Joey, was picked up once for recovering stolen property. The case was dropped, but Barajas is aware of how close her nephew came to getting derailed.

Barajas learned from the scare and now pays special attention to younger relatives of homicide victims — youths like Jorge Garcia, whose brother was murdered and whose family found themselves referred to LAURA.

During a check up on the family months later, Barajas noticed he wore all black and sported a fresh tattoo on his right forearm. Barajas swiftly encouraged the family to have Garcia change schools, arranged to put him in a Gang Reduction Youth Development program and visited the family on a weekly basis. Barajas proudly notes that Garcia is no longer tempted to join a gang, has taken up boxing and wants to get the tattoo removed.

Barajas uses her own experiences with grief to anticipate the needs death-affected families aren’t aware they need. The isolation that drove her to form LAURA didn’t stop at advocacy: Barajas said she needs every victim of random violence to know that they weren’t alone. Two months after Laura was killed, Barajas took to the streets.

A Fair Gives Voice

“Homicide is so common that families are used to it,” Barajas said. “The fair is us saying, ‘it’s not right.’”

On May 17, 2007, Barajas gathered friends and community members for a small neighborhood fair. More than a memorial, Barajas started the fair to provide survivors with resources to move forward with their lives. Barajas holds the LAURA Unity and Peace Resource fair annually on the closest Saturday to March 18, when Laura was killed. More than a support network, the fair is a call to action to address the lack of services and resources.

“We don’t have a Boys and Girls club, we don’t have a YMCA, but we’re surrounded by some of the richest areas in the community,” Barajas said. “What do other cities have for their youth?”

Keeping youth occupied is important, whether in keeping parks open through Project LAURA’s partnership with People for Parks or in Barajas’ own efforts to line up jobs for case families.

“When a kid has a job, he doesn’t have time to get caught shoplifting,” Barajas said.

Project LAURA offers collaborative meetings at Fred Roberts Park every Thursday at 5 p.m. and other local outreach programs. But the fair has also attracted large-scale attention, regularly drawing Councilwoman Jan Perry and Speaker of the Assembly Jon A. Pérez. This year’s Peace Fair also featured State Controller John Chiang, but the honored guests always include Joey, Denise, Mikey and Brian — Laura’s children.

For the fourth year in a row, Barajas gathered the community to support its members’ personal grief. She gathered them at the corner of Vernon Avenue and Long Beach Boulevard, where Laura was killed.

The pain never leaves, Barajas says, but being there for families grieving from loss reminds all involved that they are not alone.